|

Trophies like this are often lost to netting blunders.Netting a fish is elementary in concept, providing the likes of small snapper, grunts and seatrout are the end game. However, netting challenges increase with the fish’s size, attitude and environment. For example, try netting a trophy cobia, snook or striped bass in a strong current, from an anchored boat.

Out of Tears

In the mid ’90s, when Chris Woodward and I fished off Jensen Beach, Florida, with Capt. Mike Holliday, the seatrout bite was slow, so I removed my leader and tied the topwater plug directly to the 8-pound mono line. As luck would have it, a monster snook struck the plug. A long fight and chase ensued, but the snook eventually tired.

With Holliday on the poling platform, Woodward had the pressure of netting an estimated 35- to 38-pound snook. She lowered the net, and I began to lead the snook into it, then the treble hooks snagged in the mesh; only the head of the fish was in the net. Panic mode ensued. One violent head shake later and the snook disappeared, leaving only my plug in the net. Woodward and I chuckle about that every now and then, though she more than me.

.jpg)

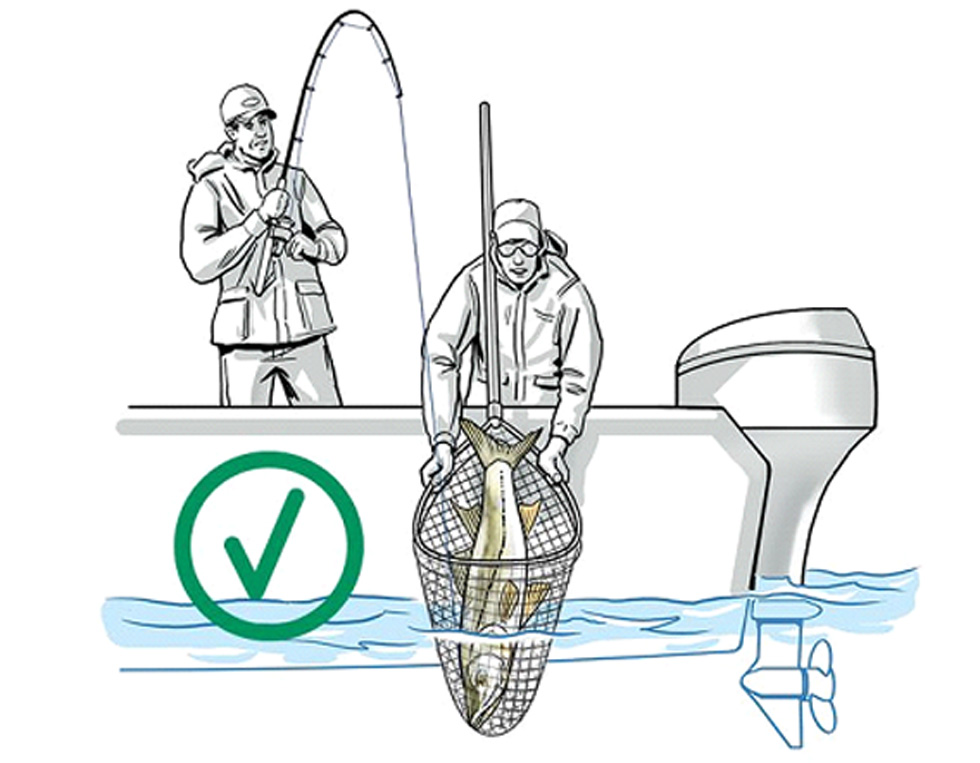

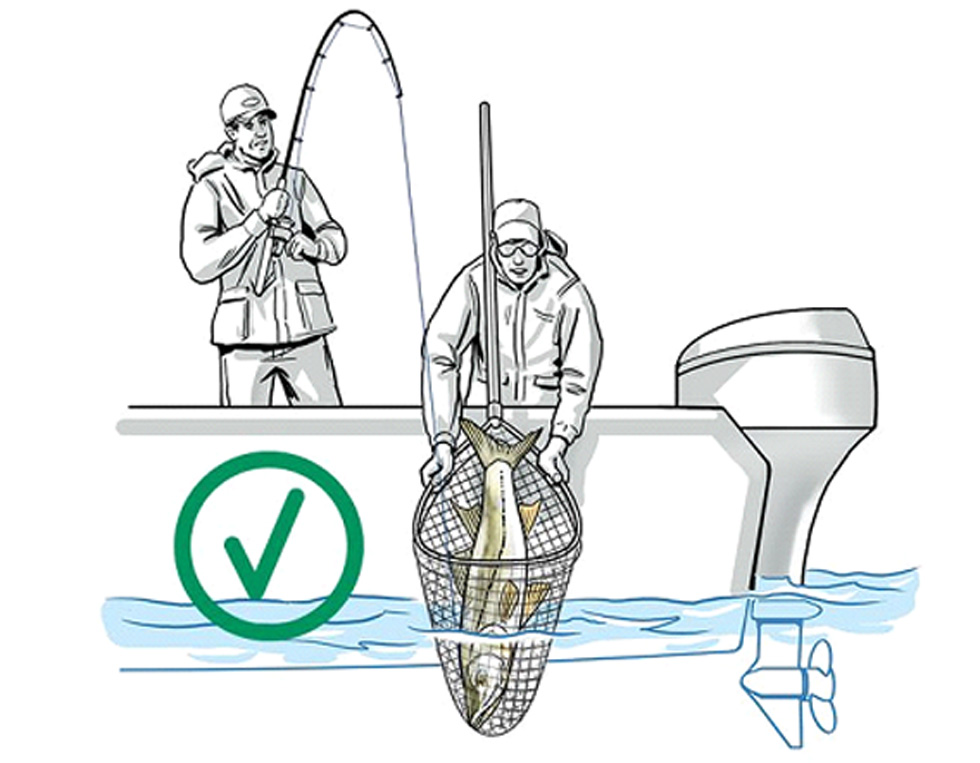

Successful netting is more a matter of leading a fish head first into the waiting net than it is chasing them down. Stay calm, move slowly and smoothly, and wait for the opportunity to let the fish swim into the waiting net.

Steve Sanford

Size it Right

The net’s size along with its strength and style determine its potential for success. Some pros carry two or three different sizes, based on ¬targeting trophy-class inshore and even ¬offshore fish. With the latter, netting is ¬often more efficient than gaffing, with school dolphin (especially those being released or tagged), blackfins and small yellowfins (to avoid flesh damage with a gaff), mackerel, cobia, grouper, snapper and tilefish serving as prime examples.

Zack Hoffman is one of Virginia’s premier trophy-cobia guides. Recently, the Virginia Marine Resources Commission passed a no-gaffing rule for cobia. Therefore, Hoffman has honed the art of netting cobia. And, incidentally, his largest cobia to date, a brute weighing 96.8 pounds, was netted. “The bigger the loop, the better,” says Hoffman. “And that applies to any type of fish. In our case, we see a lot of large cobia, some 50, 60, 70 pounds or better. A fish that large has to fit easily within a net, not get forced into it. Then the basket has to be deep enough to contain fish that large. My net has a diameter of around 3 feet.”

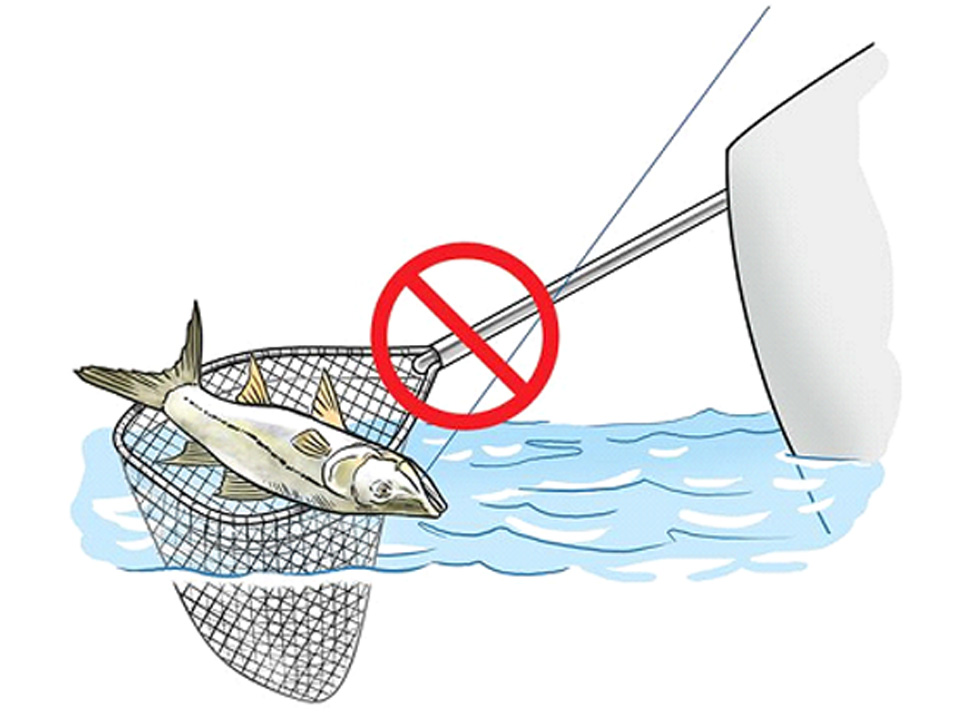

Once the fish is in the mesh, work your hands down the handle and grab the hoop before lifting it aboard.

Steve Sanford

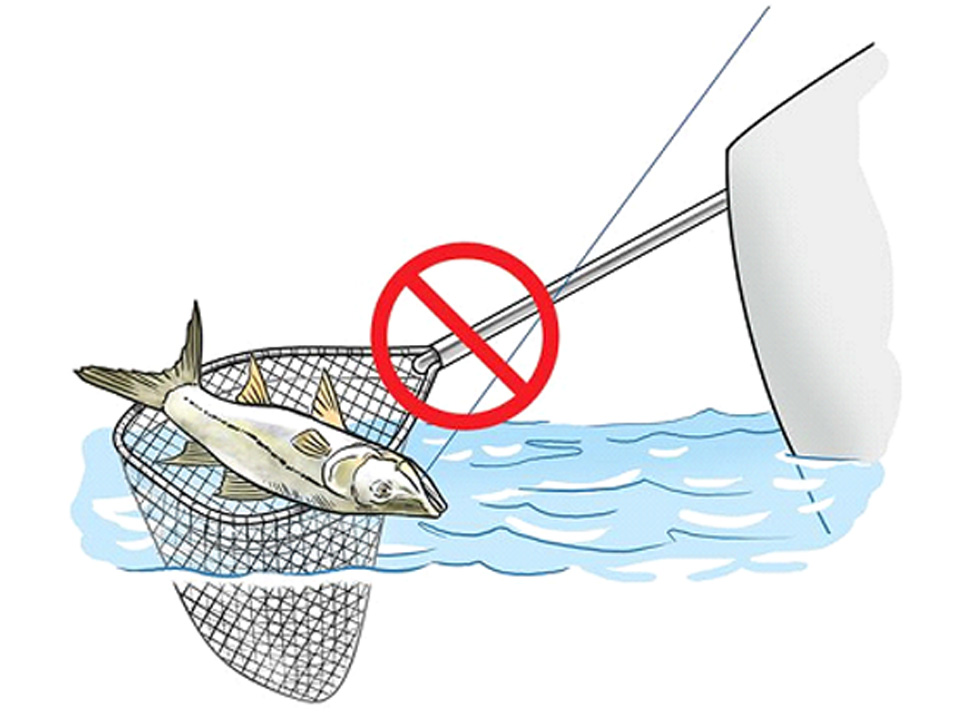

Attempting to hoist the fish by the net handle may result in a broken handle and certainly a lack of control over the landing process.

Steve Sanford

Superman Components

Given the battles with large “green” fish, the net’s rim, handle, components and mesh have to be top-grade. Avoid bargain-basement nets, which may buckle, bend or pull apart on a big fish.

A couple of seasons ago, Harry Vernon III and I went snook fishing in North Biscayne Bay out of Miami. My net was suitable for the inshore groupers, seatrout and smaller snook we had been catching. The big snook Vernon hooked was about to expose my net’s shortcoming.

Vernon pressured the big snook away from a dock, mangroves and a bridge. The net’s diameter was large, and the snook fit into it easily. But as I lifted the big snook from the water, its sharp gill plate sliced through the mesh. We were fortunate in that the snook hit the deck and not the water. Yet the incident made me research net materials that are more durable than standard nylon.

Hoffman prefers a black coating on the nylon mesh, claiming hooks are less likely to snag in it. Many high-performance and conservation nets also feature such protective materials and coatings to significantly reduce the chance of abrasion to fish destined to be released.

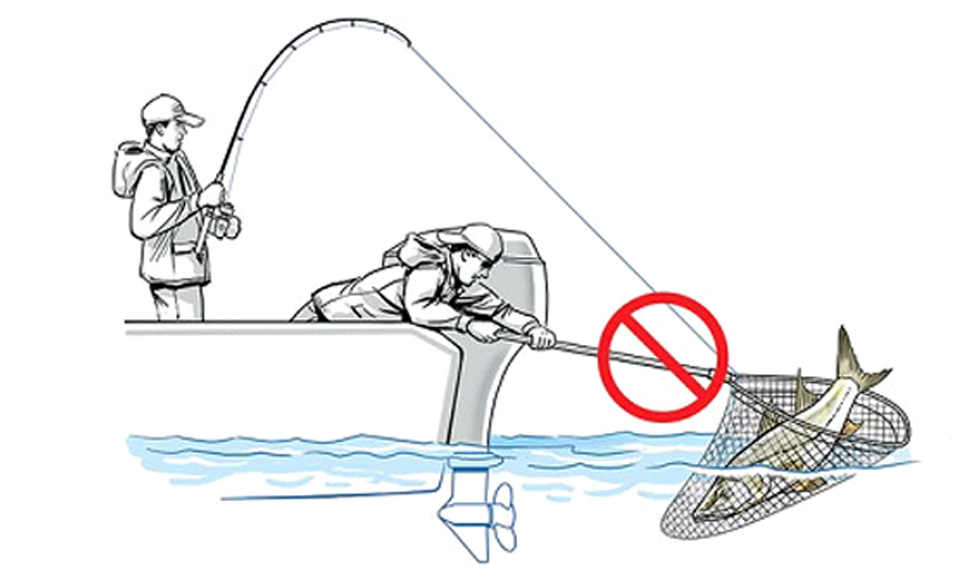

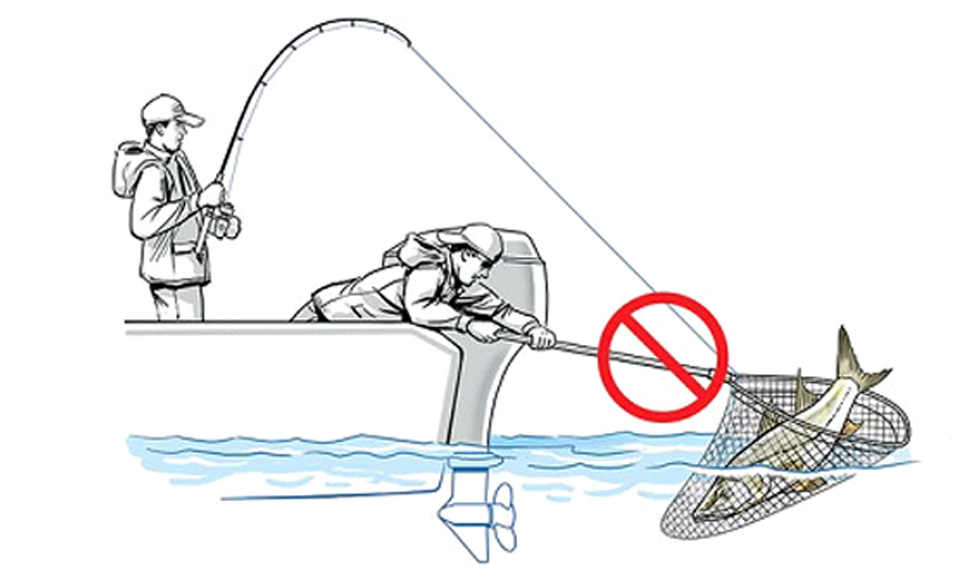

A wild stab at the fish as it swims by generally results in a missed attempt and often a lost fish. Never attempt to chase the fish down to net it tail-first, and resist the temptation to make a wild swing in hopes you’ll get the job done. That seldom works, and it presents abundant opportunity for the fish to escape or break off.

Steve Sanford

When it Counts

“It’s challenging enough for seasoned anglers to net big cobia,” says Hoffman. “I take charters, so imagine what it’s like for me to get people who aren’t used to netting these fish in tune with it. But we make it happen.” Hoffman’s systematic approach to netting applies to numerous species.

“The first thing is to not let the fish see the net,” says Hoffman. “The fish will freak out. Keep the net out of the water until you need it. Also, a net waiting in the water is hard to manage, given its size and the current. You lose the ability to make any sudden ¬compensations.”

Hoffman agrees that a fish should always be led into a net headfirst. Never try scooping one up from underneath; one kick of its tail and off it swims. As for hooks snagging during this process, Hoffman reiterates the importance of first sizing up the fish, waiting for it to swim to you, and then patiently taking your shot. “Don’t rush a net shot,” says Hoffman. “If need be, let the fish settle some more. A calmer fish will be easier to lead into the center of a big, wide net. Then, exposed hooks won’t snag mesh. If a hook snags, chances are it will be deep in the net and too late to benefit the fish.”

Fish Curls

Once a fish is subdued, don’t lift the net from the water and try swinging it into the boat. With a heavy fish, leverage will be compromised and ¬struggling will ¬ensue. Once a fish thoroughly enters a net, lift upward and then grasp the rim near where the base affixes to the handle. Then lift it straight up from the water.

A “fish curl” accomplishes three things. First, it settles the fish deep into the net, practically eliminating it ¬flipping out. Second, the leverage advantage remains with the netter; less effort is required to lift a fish from the water. And finally, the netter retains control of the fish; it can then be unhooked and placed back into the water for a release, or deposited on ice.

|

.jpg)