Celebrating

|

Learn To Chase Hooked Fish

|

| Make boat handling part of your fish-fighting strategy |

| by George Poveromo |

|

Chasing after a powerful, long-running fish is common sense; that is, unless spinning tales of how a big one spooled the reel and got away is more your speed. Pursuing a hooked fish entails much more than simply trying to keep line on a reel. It’s an acquired skill that provides an angler with advantages to beat large game. WINNING MOVES Battling a big fish is like a choreographed dance. Knowing how to counter the fish’s moves and reacting quickly are the keys to success. Release the anchor quickly, then clear obstacles, like additional lines on the water that could result in tangles. Establish some hand signals ahead of time to tell the skipper how to proceed during the battle.  |

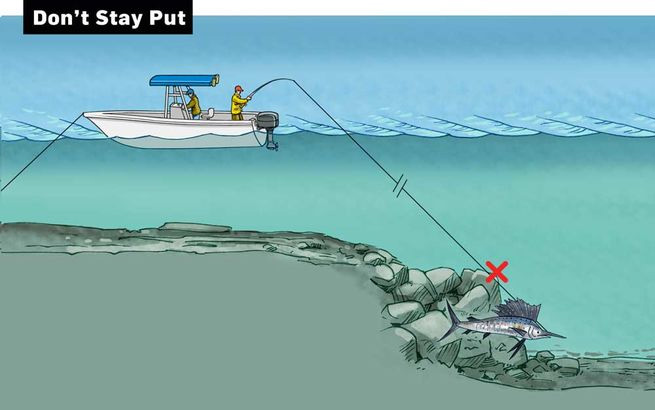

| At anchor, you can’t keep a fish from spooling you or breaking you off on a ledge or structure. |

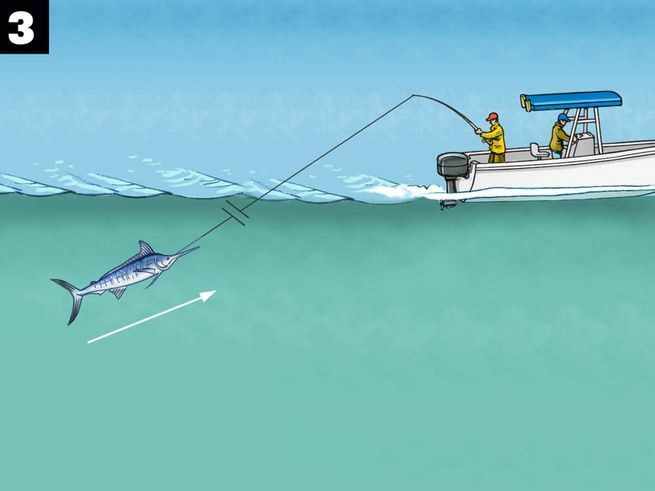

| THE DYNAMICS Remaining at anchor or drifting as a fish strips off line presents two threats. Initially, as the diameter of line on a spool decreases, drag pressure increases, which threatens the line. Furthermore, excess line pulled through the water creates even more resistance and drag; if an angler doesn’t back off the drag to compensate, the line parts. And with a fast-running fish, swift reaction by the angler is warranted; there’s little time to waste. Next, if fishing along drop-offs, reefs or other high-profile bottom, there’s the risk of a long- and deep-running fish dragging the line over such structure and parting it. What’s more, when a fish is far from the boat, it has the advantage, and the angler has little control over it. |

|

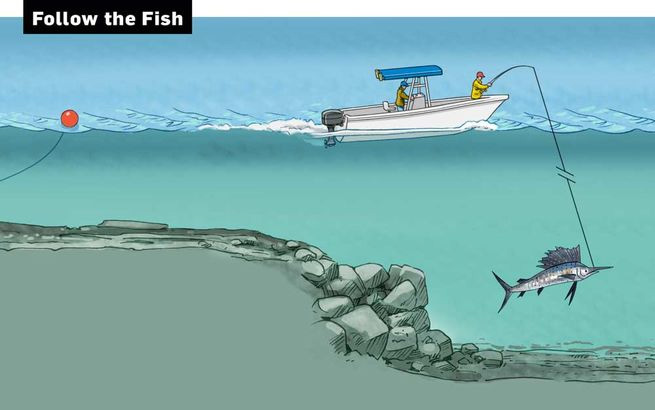

| Use a release buoy to free the boat quickly and give chase. |

| GET GOING Precisely when to pursue a fish hinges on the environment, strength of the line and size of the fish. For example, when live-baiting sailfish with 12- and 20-pound gear, we’ll give chase if a fish strips a third to half the line from the spool. This enables us to regain control and pressure the fish for a quick release without exhausting it. This is in open water, with no structure threats. At anchor, with a stationary boat and structure below, the task becomes more complex. After anchoring, make sure the entire anchor line is accessible, then secure a float ball or large boat fender to the bitter end. Should a large fish speed off toward the horizon, simply start the boat, toss over the rode (the poly ball or fender will keep the line afloat and save your spot for the return) and give chase. If a large fish shows no signs of slowing, give chase when it strips one-third of the line from the spool. The goal here is to rapidly close the gap so the boat is nearly on top of the fish. Doing so results in the fishing line entering the water in a more vertical angle. With the line angle more vertical — versus horizontal, as it would be if the boat remained at anchor — there’s less risk of it parting on sloping bottom, coral heads or rubble. Recently, while anchored in Bimini, shooting a TV show episode, I hooked a large king mackerel on a light spinning outfit. With a camera boat anchored alongside of us, tossing the anchor rode wasn’t practical. I needed luck to land this fish. To maintain the most vertical angle I could, I stepped up on top of the cooler and raised the line high overhead. To my surprise, especially after the fish dumped three-quarters of the line off the reel, we caught the huge king, which scaled 55 pounds. MAINTAIN PRESSURE Chasing fish keeps a safe amount of line on the spool and the angler close enough to it to exert control. However, there’s a balance that must be maintained. Initially closing the gap on a fish is one thing, but — once out of danger — constantly chasing it won’t do much to wear it out. It’s essential to let a fish run out line and tire itself. After initially closing the gap to get out of danger, fight the fish from a stationary boat. Keep the heat on and gain line at every opportunity. By slowing the fish’s forward progress, less water will flow across its gills and it will tire faster. Should it take off on another run when you’re in open water, let it go, then resume the pressure once it stops. If it takes an excessive amount of line, have the boat slowly close the gap as you maintain pressure. Often when the boat approaches the fish, it spooks and takes off, which could be a good thing. The cycle of letting the fish run, then applying pressure when it stops takes a toll, often rapidly. This past September off Prince Edward Island, Canada, Capt. Mark Jenkins employed this very tactic to help me score two giant bluefins: a 600-pound-class fish we released and a 701-pounder we boated. In each case, he’d let the giants strip off a few hundred yards of line while I maintained heavy pressure from the chair. When the fish stopped, I’d go to work in the chair, pumping and gaining line where I could. After several minutes of working the fish, Jenkins slowly motored toward it as I continued applying pressure and gaining line. He’d then attempt to get right above the tuna, which startled it and provoked another long run. This well-thought-out game plan enabled us to beat each fish within an hour. Step One: Planning the Fish |

|

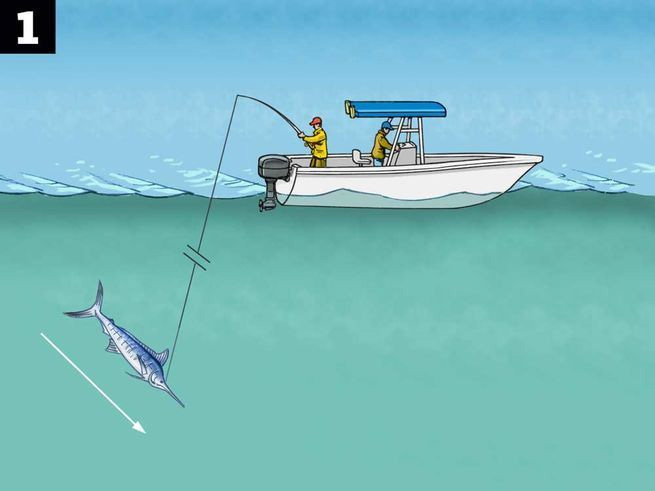

| When a fish sounds, you’re in for a long, arduous fight if you settle for an up-and-down battle. |

|

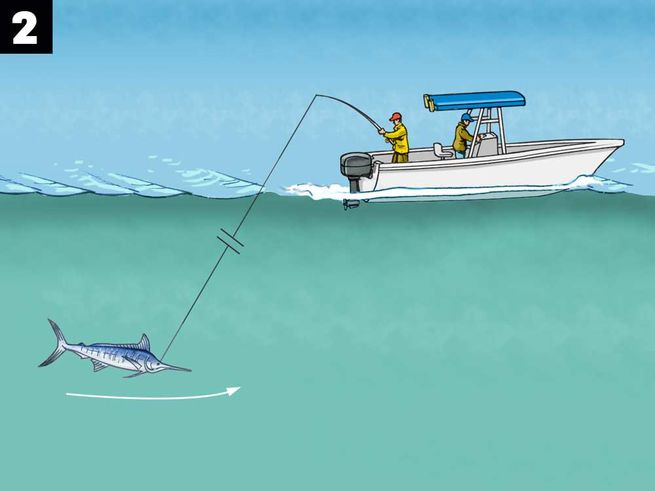

| Keep the pressure on, but when the fight comes to a stalemate, slowly motoring ahead changes the line angle and often elevates the fish’s head. |

|

| Steady pressure at this stage planes the fish toward the surface as you gain line. STUBBORN STREAKS Often a large fish sounds and holds in the depths. It’s here where patience becomes a virtue, along with some stalemate-breaking tactics. With the boat above and just ahead of a fish holding in the depths, maintain pressure and claim line when possible. As tired as it is, the fish should be moving slowly forward to gain oxygen. Whether the pull is directly from above or in front of the fish, the pressure limits its forward movement and the flow of water and oxygen across its gills. You’re tiring the fish, though it may not seem evident at the time. If you’re having difficulty gaining line, cease trying to keep the boat above or in front of the fish. Rather, let it swim off while the boat remains stationary. Sometimes the change in the angle of pull, be it ever so slight, is enough for the fish to alter its tactics. It could pick up speed and head toward the surface, clear the surface, or just swim faster. Regardless, this breaks the stalemate and further tires the fish. The result: substantial line gains for the angler. Planing a fish is sometimes required, especially for a large shark, swordfish, marlin or tuna holding near a thermocline deep in the water column. As a last-ditch resort, slowly creep the boat forward as line leaves the reel. Try this in 200- to 400-foot increments, then slowly back down on the fish while applying heavy pressure to reclaim line. Sometimes this moves a fish to higher levels within the water column and eventually to the surface. I employed this tactic five years back to plane a big swordfish to the surface for Carl Grassi, after a fight that spanned six hours and over 26 miles of ocean. Grassi battled his fish on 80-pound stand-up gear, only to enter a stalemate near the end. The fish couldn’t be budged, despite our tricks. We attempted to plane it, as outlined above. The gains in line were painfully marginal, but we were gaining. Some 30 minutes into the planing routine, a huge sword popped to the surface. We fly-gaffed and boated the fish. It weighed 380 pounds on the scale at Bud n’ Mary’s Marina in Islamorada, Florida. The planing move paid dividends for us that day. |